Boat Building & Net Making

Adapted from the papers & photographs of my late Grandfather

William Frederick IVEY

1903-2000

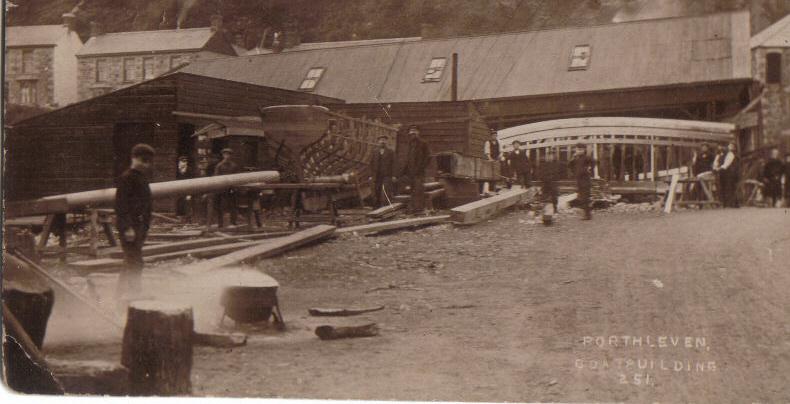

BOAT BUILDING

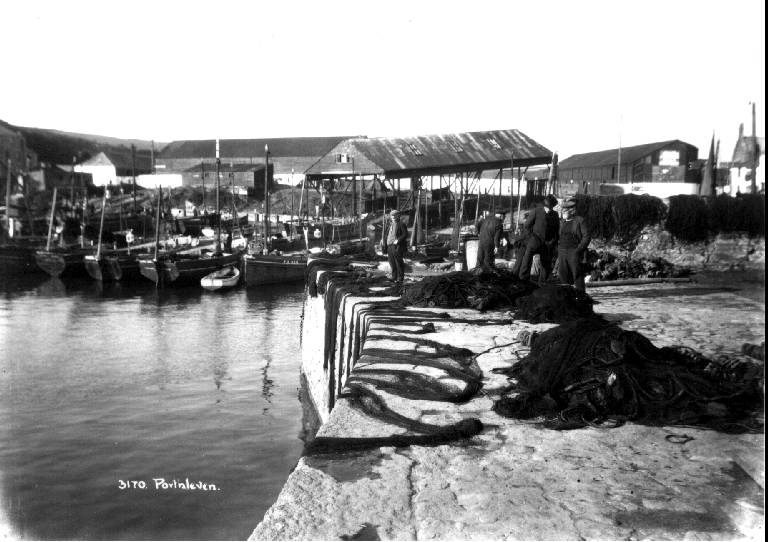

Linked very closely with fishing is boat building, an old established industry dating back to 1850. Messrs. Kitto & Sons were the principal boat builders. During their years of business they turned out from their shipyards, fishing boats for Lowestoft, Yarmouth and Aberdeen, as well as boats for Cornish fishing ports. They also built some boats for the Hudson Bay Company, Newfoundland.

The boat-building yards at Porthleven employed many hundreds of men at one time and another. On serving an apprenticeship, many builders went into Government dockyards, and others found employment in the shipyards of America.

Fishing boats of all descriptions, and pleasure craft of every type were turned out from the boat-building yards. The late Earl de la Warr, while spending a holiday at Porthleven some years ago, had a beautiful yacht built, The Lady Hilda.

In the 1914-18 war some important boat-building contracts were carried out for the Government.

Unfortunately, the time came when the fashion in fishing-boat building changed from wood to steel and on top of that, in 1922 depression came to the herring trade. This double misfortune put the Porthleven boat-building industry out of action. The old established boat-building yards have now disappeared and boat-building at Porthleven is now extinct.

Postcard sent by Kelly O`Connor, Canada

MY EARLY RECOLLECTIONS

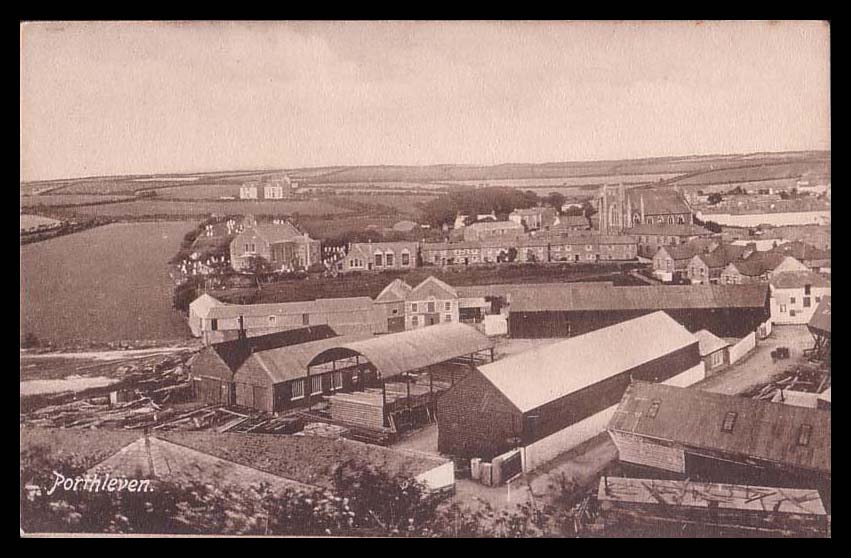

I came to live in Porthleven in 1935 and discovered a very strange state of affairs. At the harbour head there was a large, by local standards, ship or boat building shed with the name BOWDEN painted on the roof in very large white letters and easily discernable at many vantage points in the village.

There was also a `Steam Box`, a contrivance to accommodate the heavy planks which went into the construction of the boats on the stocks in the long sloping shed, which reached almost to the waters edge at normal high tides.

These planks were subjected to a thorough process of steaming in a long box shaped container, longer than the plank itself. When sufficient time was deemed to have elapsed to process the wood plank, each piece was hurriedly removed by a number of men, each wearing padding and protective wear to their hands.

Even Porthleven men, accustomed as they might have been to handle hot pieces of timber, would not tackle this maneuver without ample protection.

With tapping and banging the piece would be secured with heavy copper nails on to the rib of the craft under the expert eye of the foreman. The process of caulking and pitching would follow and the whole performance would be repeated as the boat gradually took shape.

There was a weighbridge associated with the local timber yard of Messers Harvey & Company sited in the roadway. All these items of trade and industry were the life stream of Porthleven. The strangest and perhaps the most puzzling of all to the initiated was the lack of explanation of the reason for the terrible state of the short length of roadway from the Square to the corner at the end of the harbour head. This portion was administered by Harvey & Co, who would not carry into effect repairs so urgently needed. When rain fell large pools of water had to be negotiated and at one spot vehicles had almost to perform an `S` bend to eliminate the possibility of becoming `stuck`.

To maintain their rights, the owners used to close the right of way to all traffic one day a year and even a public service vehicle was not excused this insistence of the Company in establishing their `rights`. This state of affairs existed for a while but eventually it was all sorted out. The weighbridge was dismantled and removed. The steam box together with the boat building shed also disappeared

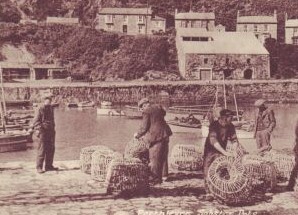

NET MAKING

Coupled with boat-building was net-making. It was the firm of Kitto s who were the pioneers in this business. The first net-making loom in Cornwall was installed in 1850. The firm made nets for all the big fishing ports of the country, and during the war employed 1,000 cottage workers in making camouflage nets and other war paraphernalia. But it eventually met with crippling competition. Japan was making nets in such mass production that no British manufacturers could compete. The net machine which, for 109 years had done such yeoman service, was dismantled and sold for scrap, and the old firm of Kitto’s closed down in 1959.

KITTO`S OF PORTHLEVEN

Adapted from an article first published on Thursday 29th October 1959 in “The CORNISHMAN” newspaper)

When in 1847 the King of Norway sent a testimonial to a Cornishman in recognition of his gallant services in the rescue of lives from the Norwegian schooner “Elizabeth” wrecked in Porthleven the previous year, the recipient was Richard Kitto, a native of Breage.

Kitto’s feat of gallantry was probably his first successful endeavour in the public eye, but others were soon to follow and when, in 1850, he started a boat building business at Porthleven, there opened a chapter of the port’s history which was to continue for 109 years. The story can now be told with the closing of Messrs. Kitto and son on the retirement, because of advancing years, of the founder’s grandson, Mr. James Richard Kitto.

Before embarking on his own account in 1850, Richard Kitto served his apprenticeship at Symons’ yard at Penzance. For a year or two he went to sea in the Mercantile Marine, but returned to set up business ashore. 1850 was a crucial year to “launch out” in industry at Porthleven, because in 1843 and again in 1852, Porthleven harbour, the basis of Mr. Kitto’s aspirations, came up for auction as a result of trading depressions, but these events, apparently did not deter the indomitable shipwright and he began by building small coasting schooners of about 50 tons and also fishing craft, principally for the Cornish ports.

At the onset, he envisaged a potential market for net making and in 1853 he was responsible for bringing the first net making loom into Cornwall. The loom came from Bridport and was installed in a shed at the rear of his residence from where the net making business began. Porthleven was now in a position of being able to build the boats and equip them with sails and nets: a unique achievement for a village of its size.

Richard Kitto·s boat building and net making went hand-in-hand to meet increasing demands for craft of varying kinds. Orders came from South Coast ports, including Ramsgate, Brighton, Folkstone, and from East Coast ports of Lowestoft and Yarmouth. The firm also did considerable trade with France for the building of the ·Dandee· and ·Yorkee· class of fishing vessels. The Porthleven fleet which sailed to Aberdeen in search of fish was evidence of the sound craftsmanship of Kitto·s boats; many orders came from the Scottish ports and Kitto·s adapted themselves to the transition from sail to steam and motor driven boats. They built a number of steam drifters and those for Lowestoft and Yarmouth were among the first to operate on the East Coast. Portheleven built steam trawlers were also provided for the well known Aberdeen Glen Line Company. They cost £2,100 compared with about £25,000 today.

At the end of the century, Porthleven was an extremely busy port, with Kitto·s employing over 100 shipwrights and subsidiary trades from within the village and district. Timber was obtained mainly from the estate at Trelowarren and, occasionally by coastal route from Exeter and Southampton. Gangs from the yards would cut the trees at the local estate and after felling, the huge trees were transported on long wheel base wagons over rough roads and hauled by teams of six, and sometimes 12 horses, Messrs. Tyacks of Carleen, were regarded as the biggest carters in the county and the arrival of their wagons in the village was an impressive sight. The task of the sawers too, was a long and arduous one, often involving an operation lasting from early morning until late in the evening.

Among the biggest commissions undertaken by Kitto·s was the building of motor vessels for the Hudson Bay Company and designed for their fur trading expeditions in the Arctic. The first of two vessels, the Fort Churchill was completed in 1913 and she left Porthleven in July on the start of her long voyage. In September of that year she was laid up in ice in the Far North and in the November was carried away when the ice snapped. Nearly 12 months later in August 1914, the Fort Churchill was found 800 miles away, off Greenland, with her hull in perfect condition, an event which brought immense prestige to the Porthleven builders.

Before the discovery, however, the Hudson Bay Company had placed an order for another vessel, the Fort York. She was completed just as the First World War broke out and was sailed to Falmouth for clearance. Her departure resulted in an amusing incident. She had been given a code flag by the Admiralty authorities and had sailed round the Lizard to anchor off Porthleven for a farewell celebration. In the meantime the allocation of her code flag had not been reported to the coastguards, who read it as having its International Code significance ·I require the service of a doctor·. Accordingly, coastguards and medical assistance was forthcoming to the Fort York as she anchored off Porthleven, but there was both relief and amusement when the purpose for wearing the flag was revealed.

As well as the various fishing and commercial craft, Kitto·s built a number of yachts for services far afield. Some of them eventually competed in the famous Keil Regatta and there was intense delight when the Commodore of the Keil Committee placed an order for his personal yacht. The building of this yacht was considered of great importance and prestige. Work was about to commence when a European incident intervened. The heir to the Austrian-Hungarian throne, Archduke Ferdinand, was murdered in June 1914 and the Commodore was prompted to write Messrs. Kitto and Son advising the delay in building of his yacht until it was seen how the European situation was going to turn.·

World War 1 followed in a few weeks and the men were employed instead on work for Admiralty contracts: barges, pontoons and numerous small craft.

The immediate post-war years proved fatal to the industry: ·fashions· had changed and the herring trade depression finally forced the closure of the boat building interests of R. Kitto and Son.

In the heyday of shipbuilding at Porthleven, as many as twenty apprentices were employed by Kitto·s and when trained were regarded as among the best to be found. From time to time, many went to work at other yards; a number also went overseas to the Camden shipyards in the USA, but wherever they went, the reputation of Kitto and son was an acknowledged passport for employment. Many became foremen of their respective yards and each enjoyed the respect and prestige they had inherited from their native village.

Fortunately, the business of net making never suffered to the same degree as ship-building from the post-war depression, for when fishing net orders declined, the firm was able to direct its resources to the manufacture of netting for the commercial market, and consignments were sent to all parts of the British isles. The products ranged from nets for horticultural purposes to the supply of goal nets for the famous Arsenal Football Club.

Another branch of the firm·s activities was the curing of pilchards. When, at times, the Porthleven fleet landed enormous quantities of pilchards, Kitto and Son could handle as many as 1000 barrels for their storage tanks. The fish were salted-in for a three-week period and then packed for shipment to Italy. The fish curing industry was relatively short-lived as foreign competition increased and the Italians began to enjoy a better standard of living.

When the Second World War came the resources of Messrs. Kitto and Son were once more geared to the war effort and at the peak of hostilities the firm employed as many as 1000 cottage workers in the manufacture of camouflage nets in addition to the production at the firm·s works of these and other paraphernalia. In the immediate post-war years, a steady demand for nets for the fishing industry kept production at a good level but the gradual effect of foreign competition and the wider use of automatic looms had a serious effect. There was a remarkable upward trend in prices too. A pilchard net today costs £26 compared with 75 shillings (£3.15s) in 1938. In 1872 the net would cost 35 shillings (£1.15s).

Recently, the looms which still produced fishing nets with a marked degree of greater precision than that made by the automatic machine were sold to the scrap merchant. The looms were in good working order and included the original loom which came from Bridport over 100 years ago. Now, with the transfer of the premises to a newly formed company as carpet manufacturers, the retirement of Mr. James Richard Kitto marks the end of a chapter of Cornish industry.

The new company of Bradshaw Ltd, in addition to manufacturing carpets, are also producing fishing nets.

·The Cornishman· Thursday 29th October 1959